PALANTIR

Text of our KONP leaflet given to people attending the Financial Times Festival (and others enjoying Hampstead Heath)

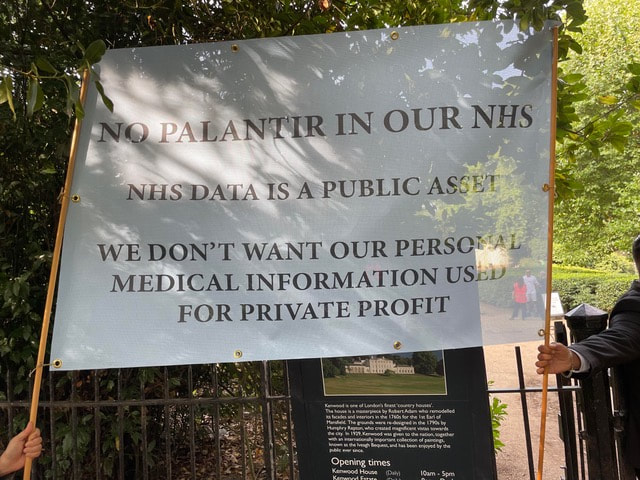

NO PALANTIR IN OUR NHS !

NHS DATA IS A PUBLIC ASSET. WE DON’T WANT IT USED FOR PRIVATE PROFIT.

Palantir is a secretive US spy-tech business founded by Trump-supporting Peter Thiel. Its CEO is Alex Karp. It is the front runner for a 5 year contract worth £360 million to provide the underlying operating system for almost the entire NHS. This will allow it unrivalled access to our personal health information, and raises concerns about privacy and confidentiality. There are also obvious dangers of the NHS relying on a single private company for its key functions.

We don’t want private companies having this kind of access to our personal data, let alone a US-based company whose core business is providing big data and surveillance support to military, security, intelligence and police agencies.

Sign the ‘No Palantir in our NHS’ petition at https://nopalantir.org.uk

The NHS holds huge and valuable sets of data, including medical information about each one of us. If used responsibly this data can help improve care and develop new treatments. It should be used for the public good but private corporations like Palantir plan to make huge profits from our data, either from contracts for data services such as processing, or to develop commercial products.

‘Trust is the beating heart of the NHS. There is no public health without public trust ..Palantir fails the trust test. It has spent most of its history helping the powerful abuse the powerless...A company like Palantir has no place in our NHS. Instead, we could build up the capacity of trusted NHS staff to use data well and improve the NHS’s own data infrastructure.’ (Foxglove, a non-profit that aims to hold big tech and governments to account.)

NO PALANTIR IN OUR NHS !

NHS DATA IS A PUBLIC ASSET. WE DON’T WANT IT USED FOR PRIVATE PROFIT.

Palantir is a secretive US spy-tech business founded by Trump-supporting Peter Thiel. Its CEO is Alex Karp. It is the front runner for a 5 year contract worth £360 million to provide the underlying operating system for almost the entire NHS. This will allow it unrivalled access to our personal health information, and raises concerns about privacy and confidentiality. There are also obvious dangers of the NHS relying on a single private company for its key functions.

We don’t want private companies having this kind of access to our personal data, let alone a US-based company whose core business is providing big data and surveillance support to military, security, intelligence and police agencies.

Sign the ‘No Palantir in our NHS’ petition at https://nopalantir.org.uk

The NHS holds huge and valuable sets of data, including medical information about each one of us. If used responsibly this data can help improve care and develop new treatments. It should be used for the public good but private corporations like Palantir plan to make huge profits from our data, either from contracts for data services such as processing, or to develop commercial products.

‘Trust is the beating heart of the NHS. There is no public health without public trust ..Palantir fails the trust test. It has spent most of its history helping the powerful abuse the powerless...A company like Palantir has no place in our NHS. Instead, we could build up the capacity of trusted NHS staff to use data well and improve the NHS’s own data infrastructure.’ (Foxglove, a non-profit that aims to hold big tech and governments to account.)

Palantir, protests and why we should hear more not less from the people running big data

By Gillian Tett 7.9.22 FT and also in FT Magazine 11.9.22

When the American entrepreneur Alex Karpand the PayPal billionaire Peter Thiel co-founded a data analytics company 18 years ago, they decided to call it Palantir.

At the time, the name — a reference to the palantíri, the seven “seeing stones” used in The Lord of the Rings to monitor the world from great distances — was considered whimsical by some, downright cute by others. Today, it has turned into rather a double-edged sword. Just as the stones in Tolkien’s novels were used for both good and evil, so the modern Palantir inspires admiration but also loathing.

Last week, I interviewed Karp at the FT Weekend Festival in London, where a group of angry protesters had assembled. The reason? During the Covid-19 pandemic, Palantir was asked by the UK government to run its vaccination data platform. “If you were vaccinated in the UK, you used [us],” Karp told the audience.

Palantir is currently bidding for a $360mn contract to manage more NHS data. It seems likely to win given that the Covid platform worked well. Indeed, Palantir has already poached senior NHS officials. But part of what is sparking protests is that the company was initially funded by the CIA, and, Karp tells me, about 50 per cent of its revenues still come from security groups such as the FBI, Nato, the British military and forces in Ukraine.

This is not an outlier for American tech companies. Innovations such as GPS were born in military circles. And one reason why companies such as Palantir move from military into civilian work is that government contracts can be capricious.

In Karp’s eyes, the fact that Palantir partnered with the CIA should reassure, rather than distress, NHS users in the UK. After all, he told me, the CIA will only deal with entities that can keep data ultra-secure and segmented — and who will not sell this data to others. Presumably, this is what the NHS wants too.

But the protesters decry the group as “a huge, secretive US spy-tech business founded by Trump-supporting Peter Thiel” and say that medical data should only be used “for the public good”, and thus not handled by any profit-seeking venture. Indeed, one protester feels so strongly about Palantir that she told me in an email she was “very disappointed” that the FT offered Karp a platform at the festival.

I disagree: it’s the duty of journalists to interview controversial figures. And as I discovered in my conversation, Karp defies some easy stereotypes. Like other big tech innovators, he is intense, intelligent and curious. But he also possesses a PhD in social science from the Goethe University in Frankfurt, has self-avowed leftish political leanings and professes his dislike for the arrogance and introverted nature of Silicon Valley.

He is also proudly loyal to the US government, and ready to help Washington to execute policy. Sometimes this wins accolades: Palantir’s data services apparently helped track down Osama bin Laden and are now being used to back the Ukrainian army. Other times it does not: liberals decry the use of Palantir software to track and deport undocumented migrants in the US. Whether you think it is good or bad that the company helps carry out US government business, its concern is to do so efficiently.

As to the fears about handing sensitive health data to the private sector, Palantir makes its profit through data management contracts, not from selling it on. Of course, this will not mollify its critics and I understand why. But perhaps the question that protesters should ask themselves is: if they don’t trust Palantir, who would they prefer to handle NHS data instead? A British company that may be less cutting-edge? A public sector body that might be less secure? Or the currently creaking NHS itself?

These are difficult questions. When Karp talks about keeping NHS data secure he sounds credible but we have no way of knowing exactly what happens to that data, and the lack of oversight involved when private companies take ownership of public data is concerning.

Very few voters, politicians or journalists — including myself — know how to determine what is “safe” when it comes to this rapidly expanding industry. As Karp himself has pointed out, the fact that only a tiny pool of technical experts really understands the issues poses a big challenge for modern democracy.

But that is precisely why we need to put people in his position — and their critics — on a public stage. We must also ensure there is public scrutiny of whatever contract the NHS strikes. Final control of the data should rest with the health service and its users, and nobody else. As big data keeps getting bigger, these challenges will only get harder.

By Gillian Tett 7.9.22 FT and also in FT Magazine 11.9.22

When the American entrepreneur Alex Karpand the PayPal billionaire Peter Thiel co-founded a data analytics company 18 years ago, they decided to call it Palantir.

At the time, the name — a reference to the palantíri, the seven “seeing stones” used in The Lord of the Rings to monitor the world from great distances — was considered whimsical by some, downright cute by others. Today, it has turned into rather a double-edged sword. Just as the stones in Tolkien’s novels were used for both good and evil, so the modern Palantir inspires admiration but also loathing.

Last week, I interviewed Karp at the FT Weekend Festival in London, where a group of angry protesters had assembled. The reason? During the Covid-19 pandemic, Palantir was asked by the UK government to run its vaccination data platform. “If you were vaccinated in the UK, you used [us],” Karp told the audience.

Palantir is currently bidding for a $360mn contract to manage more NHS data. It seems likely to win given that the Covid platform worked well. Indeed, Palantir has already poached senior NHS officials. But part of what is sparking protests is that the company was initially funded by the CIA, and, Karp tells me, about 50 per cent of its revenues still come from security groups such as the FBI, Nato, the British military and forces in Ukraine.

This is not an outlier for American tech companies. Innovations such as GPS were born in military circles. And one reason why companies such as Palantir move from military into civilian work is that government contracts can be capricious.

In Karp’s eyes, the fact that Palantir partnered with the CIA should reassure, rather than distress, NHS users in the UK. After all, he told me, the CIA will only deal with entities that can keep data ultra-secure and segmented — and who will not sell this data to others. Presumably, this is what the NHS wants too.

But the protesters decry the group as “a huge, secretive US spy-tech business founded by Trump-supporting Peter Thiel” and say that medical data should only be used “for the public good”, and thus not handled by any profit-seeking venture. Indeed, one protester feels so strongly about Palantir that she told me in an email she was “very disappointed” that the FT offered Karp a platform at the festival.

I disagree: it’s the duty of journalists to interview controversial figures. And as I discovered in my conversation, Karp defies some easy stereotypes. Like other big tech innovators, he is intense, intelligent and curious. But he also possesses a PhD in social science from the Goethe University in Frankfurt, has self-avowed leftish political leanings and professes his dislike for the arrogance and introverted nature of Silicon Valley.

He is also proudly loyal to the US government, and ready to help Washington to execute policy. Sometimes this wins accolades: Palantir’s data services apparently helped track down Osama bin Laden and are now being used to back the Ukrainian army. Other times it does not: liberals decry the use of Palantir software to track and deport undocumented migrants in the US. Whether you think it is good or bad that the company helps carry out US government business, its concern is to do so efficiently.

As to the fears about handing sensitive health data to the private sector, Palantir makes its profit through data management contracts, not from selling it on. Of course, this will not mollify its critics and I understand why. But perhaps the question that protesters should ask themselves is: if they don’t trust Palantir, who would they prefer to handle NHS data instead? A British company that may be less cutting-edge? A public sector body that might be less secure? Or the currently creaking NHS itself?

These are difficult questions. When Karp talks about keeping NHS data secure he sounds credible but we have no way of knowing exactly what happens to that data, and the lack of oversight involved when private companies take ownership of public data is concerning.

Very few voters, politicians or journalists — including myself — know how to determine what is “safe” when it comes to this rapidly expanding industry. As Karp himself has pointed out, the fact that only a tiny pool of technical experts really understands the issues poses a big challenge for modern democracy.

But that is precisely why we need to put people in his position — and their critics — on a public stage. We must also ensure there is public scrutiny of whatever contract the NHS strikes. Final control of the data should rest with the health service and its users, and nobody else. As big data keeps getting bigger, these challenges will only get harder.